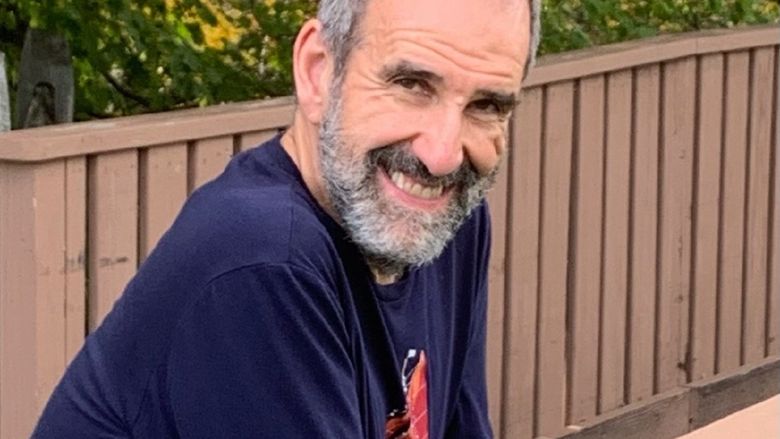

Pennsylvania Game Commission Elk Biologist Jeremy Banfield, at left, leads Penn State DuBois Wildlife Technology students in collecting data from a sedated elk near Benezette, Pennsylvania. Participating students are, left to right: Standing, Nick Michelone and Samantha Carns. Kneeling, Garrett Orcutt, Eli DePaulis and Instructor in Wildlife Technology Keely Roen.

DUBOIS, Pa. — Honors students in the Penn State DuBois Wildlife Technology program had an exclusive opportunity for hands-on learning recently with members of the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s (PGC) biological staff. The PGC is currently researching reproductive trends among Pennsylvania’s elk herd in hopes of improving the overall health of the herd and increasing the population. To that end, four first-year honors students from the program, with their instructor Keely Roen, joined Elk Biologist Jeremy Banfield and Elk Biologist Aide Avery Corondi in chemically immobilizing a cow, or female elk, so that blood samples crucial to these conservation efforts be collected.

“We collected blood samples during our hunting season for elk, which happens in the first full week of November, and we’ve been testing for pregnancy, and it’s been suspiciously low. Around 55 to 60 percent,” Banfield explained, noting that the pregnancy rates in November would ideally be at around 90 percent. “So, we are collecting blood samples now, later in the season, to see if pregnancy increased. Basically, we want to see that if you give the animals more time to breed, will pregnancy go up.”

While this research is still in its very early stages, Banfield said seeing pregnancy rates increase into the spring is not actually a positive finding. He said late season pregnancy among female elk means an increased mortality rate for their calves and hopes that most cows will be pregnant earlier in the season. Ultimately, through this research, they hope to understand why that isn’t happening.

“It’s going to depend on what we find here, what our next step is. When you have either low pregnancy or late pregnancy, it obviously influences the population. So, we are trying to deduce what’s going on here so we can hopefully correct it in the future,” Banfield said. “You want the animals to be bred in as short of a window as possible. Early on in late September is the prime period. The reason is that the rut [breeding season] is rough on both genders, especially bulls that can lose up to 20 percent of their body weight.

"Also, nature has evolved this way so that the calves that are born during the end of May, beginning of June, which is the prime time for vegetation, and that’s a good time," added Banfield. "Food is plentiful, and they can gain weight fast. If they’re born late, they don’t have as much time to gain that weight and have lower chances of survival going into the fall, so we don’t want late pregnancy. We want the population to grow; more importantly we want the natural process to work as it should, but right now it appears that it’s not.”

While these early steps of this research will hopefully reveal why these late pregnancies are happening, Corondi added that it is a confusing setback for the population of a species that otherwise is poised for great survival and reproductive success in the Commonwealth. She said, “It’s high quality forage we have here, so there’s plenty of food, a great bull to cow ratio, and no natural predators. These animals really have very few stressors, so the pregnancy rates should be higher.”

The process by which samples are collected for this research is challenging, adding another layer of difficulty for these wildlife professionals. They are specifically targeting female elk, three-and-a-half years of age and older. They must first locate a group of animals, visually identify an individual they hope to collect samples from, then close in, getting into range for a clean shot with an air powered gun that fires darts that deliver the immobilizing chemicals that sedate the elk long enough for samples to be collected. The safe range to ensure a chance at a clean shot with that device is about 40 yards. Just immobilizing the animal alone can take a great deal of know-how and woodsmanship.

“We collected blood samples during our hunting season for elk, which happens in the first full week of November, and we’ve been testing for pregnancy, and it’s been suspiciously low. Around 55 to 60 percent.”

— Elk biologist Jeremy Banfield

It was this process that Penn State DuBois honors students in the Wildlife Technology program had the opportunity to participate in, an opportunity not open to any other members of the public or community outside of PGC staff. Currently studying to work in the field of wildlife conservation, this exclusive experience gave the students the chance for a real-world look at some of the work they could look forward to completing when they enter their careers.

Freshman Wildlife Technology honors student Samantha Carns, of Clearfield, said, “It was amazing. I one hundred percent want to do it again. I have never been that close to an elk and it was so cool.”

Banfield and Corondi led the group of students from Winslow Hill near Benezette in Elk County, out into the heart of Pennsylvania’s Elk Range at sunrise. They quickly came upon a group of elk and identified a cow that fit their profile for testing. After Banfield made the shot with the dart gun, the group waited about 10 minutes before tracking the animal. They were assisted by radio telemetry that homes in on a signal put out by the dart, and used the device to help locate the elk, which was able to run a couple of hundred yards before she would succumb to the immobilization drugs.

Once located, Banfield and Corondi quickly got to work collecting blood, as well as other data from the cow. Banfield said, “While we have her down, we check heart rate, breathing, and temperature, to assure the health of the animal. We age her by examining her teeth. The blood sample is what we’re after, but while we have her there, we take the chance to assure the overall health of the elk.”

Following the collection of samples and data, reversal drugs are injected into the elk to counteract the immobilization drugs that tranquilized her. All animals studied are monitored until they’re awake and able to regain their feet. In this case, the cow elk was awake and able return to the herd within four minutes after recovery drugs were administered.

Penn State DuBois students helped the PGC staff throughout this process and in collecting data, including blood samples and vital signs, taking the opportunity for more real-world lessons that will give them experience as they go into their future careers.

Carns said, “This helped me realize what wildlife biologists actually do, and it just opened up my eyes.”

Garrett Orcutt, a freshman wildlife technology student from Rockton, Pennsylvania, said, “It was definitely one of the most awesome opportunities I’ve ever had the pleasure of being a part of. It was great of Jeremy for letting us be a part of this.”

Getting to be in such close contact to wildlife, as well as the hands-on work that conservationists do every day, was and invaluable learning experience for these aspiring professionals.

“Being that close to such a large mammal that is such a big part of Pennsylvania’s heritage really narrows it down that I want to do something in my career with big game animals,” Orcutt said.

Instructor Keely Roen said the type of inspiration and real-world experience Orcutt is thankful for is exactly why she seeks out these opportunities for her students. She said, “This gives students the chance to interact with professionals in natural resources, and to be part of an experience that they may very well relive five or 10 years from now in their careers. There’s no way to replicate that in the classroom. You have to really see it to understand what goes into something like this. If you don’t see it in person, you really don’t truly understand it.”

Getting to be in such close contact to wildlife, as well as the hands-on work that conservationists do every day, was and invaluable learning experience for these aspiring professionals.

Roen said the students participating in this experience will use what they’ve learned to help their classmates take their education one step further, as well. She said, “These honors students will do a presentation on their experience for other students in the Wildlife Technology program when we learn about chemically immobilizing deer in the fall semester, so they’ll be able to share what they’ve learned and note the differences they see between deer and elk.”

According to Banfield, the elk herd in Pennsylvania was extirpated due to overhunting in the late 1800s. Beginning in 1913, efforts to bring the species back to the Keystone State began with importing animals from other states. Between 1913 and 1926, 177 elk were introduced into Pennsylvania. That number initially grew to between 400 and 500 animals. Official yearly counts of the species began in 1971, and eventually a hunting season for elk in Pennsylvania was open in 2001 when it was determined the population increased to a sustainable number that could be managed by hunting.

Though the current pregnancy rate is alarming, importation of elk as was done in the past is no longer an option due to the outbreak of Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD). An affliction plaguing deer and elk alike, CWD originated in the west and has already found its way into Pennsylvania. There is no cure for the disease, which attacks the nervous system of the animals, and it is always terminal to those that contract it. To prevent the spread of the disease, conservationists have determined that deer and elk should not be relocated. Though it is a threat to deer and elk species populations, no evidence has been discovered that it is harmful to humans. Additionally, Banfield’s opinion as the state elk biologist is that it can be mitigated to the point of sustaining wildlife species.

He said, “Our elk will inevitably get it. When that’s going to occur is always difficult to predict. But when it happens, we have no reason to expect it will wipe out the elk population. There will be a presence of the disease that we’ll have to respond to; it’s a serious thing and we’ll keep it on the forefront. But it won’t wipe out our herd.”

Currently Pennsylvania boasts an elk population of approximately 1,000 animals.

Banfield said members of the public should be reminded that feeding elk is illegal, and in CWD areas of the state, feeding of deer is prohibited, as well. Refraining from feeding wildlife will help in stopping the spread of diseases like CWD.